|

|

|

|

From Kensington to Cambridge (via Madagascar and Yale) |

|

|

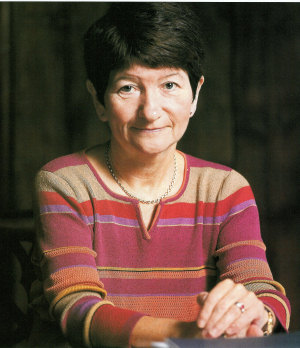

One of the most distinguished alumni of Queen Elizabeth College is Professor Alison Richard, who has been Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge since October 2003 |

|

|

Professor Richard is the first woman to be appointed to Cambridge's Vice-Chancellor role in its current form, and the only woman among the heads of Russell-Group universities. After completing her first degree at Newnham College, she came to QEC in 1969 to research her PhD in primate biology. She moved to Yale in 1972 and became Professor of Anthropology there in 1986. Between 1991 and 1994 she was Director of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, and from 1994 to 2002 she was Provost: the University's chief academic and administrative officer. Here she speaks to Christine Kenyon Jones. What led you to do your doctorate at QEC? Like most PhD students, I suspect, I didn't actually choose to come to a particular college, I came to work with a particular person, and that was John Napier : an absolutely remarkable man whom I saw as someone who would be my mentor in studying the functional morphology of lemurs in Madagascar. That was what brought me to the Unit of Primate Biology which had been established at QEC, having previously been at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. The unit was in a rather funky old coach house that had been made over from being a residential house, with a warren of charming rooms on several floors. Have you been back at all since then? No, but your question made me think I should take my husband and retrace our footsteps. Having been in the States for 30 years we haven't had time. But now that we're here and I'm just starting to imagine doing something other than scrambling to stay ahead of things, I will certainly do that. What do you remember about QEC? I remember that the College's motto was 'Keep the home fires burning'. I always thought that was a really splendid motto, and of course it came from World War I and the fact that QEC was created for the education of women in and around the First World War. I'm pleased and moved that QEC is being recognized within the King's College family. What I remember about the unit of Primate Biology is that it was full of really interesting and bright people, such as Michael Rose, who went on to become a distinguished professor of anatomy and paleanthropology in the US – and a lifelong friend. John Napier himself was a larger-than-life figure : a great anatomist who pioneered work on the evolution of the human hand. But when I was working with him he had become completely fascinated by the phenomenon of the Abominable Snowman and the Big Foot. One of the last books he wrote was called Big Foot. My name is mentioned in the acknowledgements, and I'm very proud of that! Were you convinced? Ah ... read the book! We would have these interesting people coming by who had seen what they thought to be Big Foot in the wild. I remember one man who worked for a major oil company and he more or less came in disguise, saying 'If my bosses knew that I thought I'd seen a Big Foot they would put me on medical leave of absence. So you can't quote me by name in your book, but let me tell you what I saw...'. It was extremely interesting - but it was hardly the functional anatomy of lemurs in Madagascar. How did you come to the lemurs? When I did my first degree at Cambridge I was taught by an inspiring woman called Alison Jolly, an American who did her postdoctoral work in Has anthropology changed since you were a student? Our understanding of human evolution has been transformed. New fossils have been found, and genetic analyses adds a whole new dimension to our understanding. A single skull or even a single tooth can completely change everybody's ideas. It's a problem, in truth, that there's so little evidence – that you're constantly piecing together what was happening then. As for lemurs in particular, they simply weren't much on the map in the early 1970s. There were only a handful of people who'd done serious research on them. And now there are whole programmes of research on lemur biology and behavior, so that's really gratifying, Is the fact that Madagascan lemur females are dominant over the males what made you want to study them? No. That's a coincidence. But it is a very interesting thing that the females are socially dominant, and leads one to ask why females are not socially dominant among most nonhuman primates elsewhere in the world? There are a very few species of mammals where females are socially dominant or co-equal, so what makes it different in Madagascar? There are features of the environment there that are distinctive, one of which is its unpredictability. But I doubt there is any single magic bullet to explain this unusual behavioral phenomenon, which is still the focus of a lot of research. Do you think lemur behavior teaches us anything about human behavior? It is neither helpful nor scientifically sound to make simple inferences about human behavior from the study of nonhuman primates, though there's a considerable history of doing just that. In my view, the best subject of study if you're interested in Modern human behavior is humans. However, I do think the study of nonhuman primates is useful for our efforts to reconstruct the evolution of human behavior and to understand the evolution of sociality in general. Even before you’d formally completed your PhD you were offered a post at Yale? Yes. I was phoned up by my former supervisor at Cambridge asking if I'd be interested in applying for a job at Yale. I'd actually been planning to go off to Alaska, to study musk-oxen, with a boyfriend I had at the time who'd got a job there. I said I'd be interested in applying, and where was Ya1e? And off I went, got offered the job and accepted it: never imagining that I was making a decision about where I'd be for the next 30 years of my life. Do you feel more American than British? My husband is American and our children were educated in the States. You take on the colour of the country you live in. But I grew up here and there are features of this country I feel deeply attached to. There are different features of the US that I love too, and I don't feel I have to choose between them. There's a sense of scale and community in this country. Here in Cambridge, I really appreciate the way people take the time to talk and think together across unconventional boundaries. And the things that attract you in America? It's almost the flip side of that: the vastness, the speed at which things move. That's exciting too. The British style is very different. There are Americans I've met who are frustrated in this country by the fact that it doesn't move faster, and Brits in the US who curl their lip at what they see as the brashness of it all. But I just have a deep affection for both these ways of living – and periodic frustrations with both! What part do you think that alumni should play vis-à-vis their own universities? Our alumni today were once upon a time our very bright students, and they're now very bright adults with a lot of experience under their belt. Universities have much to gain from engaging with alumni and maintaining a relationship with them, because they are our best ambassadors. And of course, one would hope that alumni will give back and invest in the university. But I think giving financially is only one piece - an important piece but only one piece – of what alumni can contribute. It's my experience that alumni also gain from the relationship – universities are interesting places to be associated with. Is there anything you think US higher education has to teach the UK? We can certainly learn from the assertiveness of US universities. We in British Universities need to stand up and say why we're important, why we matter, what we contribute. There was a period when universities didn't really get a hearing, but I do think the last decade has seen a transformation in the way in which we are being viewed. That was part of what brought me back here. But we must keep on working at this. As for educational matters more specifically there are real1y interesting questions for both countries about differences in the way we go about educating our students. Cambridge, and I think I UK universities in general, place more emphasis on learning and less on teaching; more emphasis on summative assessment and less on continuous assessment, more emphasis on going deeply into a subject and less emphasis on breadth. Here it’s a three-year course, not a four-year course. All of that adds up to two very different systems of higher education, I'm a great believer in heterogeneity and diversity, but it's also good for us to think about what others are doing and learn from each other. I noticed that you'd done quite a lot at Yale to increase the proportion of women professors, and I wondered whether you had any goals in that area here? It is indeed something very important for the institution that I take very seriously. In the last decade Cambridge has doubled the percentage of women at the level of lecturer, tripled the percentage of women at the level of reader, and almost doubled - but only to ten per cent - the number of professors. Part of that's a question of time: the number of women moving up through the promotion system. During the first year I was here there was a year-long series of workshops, bringing women from across the University together to talk about issues of gender. Interestingly, the women participating said they thought most of their concerns affected men as much as women. I was quite struck that that came out as a strong message, and we've been working to follow up on the conclusions and recommendations of the workshops. But there's a ways to go. Do you think your own example will make a difference? I'm certainly aware of the fact that I must be by definition a role model. But I don't put too much faith in the sheer fact that I'm a woman Vice-Chancellor as making much of a difference. Universities are complex organizations and you need to establish a critical mass of leadership to move in a particular direction. How do you relax? My husband and I love opera, and we love to cook. Currently we live in the vice-chancellor's residence and we have gardeners, but I do love the garden -I'm an avid gardener. I like to walk - these days, that mostly means the occasional walk in the Cambridge Botanic Garden. And of course I like to read. Being Vice-Chancellor is a totally consuming job but it is also totally interesting. I feel deeply privileged to have this position, and I wouldn't be doing anything else, but it does oust all these other lives that I would enjoy living, particularly as an anthropologist and a teacher. I do miss teaching. I rarely see students these days, and although I wouldn't say it's a regret, it is a loss that I feel. Indeed, the plan in 2002 when I stepped down as Provost at Yale was to go back to being a teacher and an anthropologist. But Cambridge turned out to be irresistible. |

| [Home] [Cttee & AGMs] [Events] [College History] [People & News] [Reunions] [Photo Album] [Envoy] |

|

This page created 25 February 2007 |